Presence in an hour

Ideas on how to be a present father.

I believe presence might be the most important idea for parents in the 21st century1. When I first truly understood presence, it felt like a secret that had been hidden from me, by the very device in my pocket.

In his famous 1890 work The Principles of Psychology, William James wrote what might be the most important sentence ever written about attention:

“My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind.”

Presence is one of those “I know it when I see it” ideas. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Before I explain it, let’s see it.

Low Presence moment

High Presence moment

Low Presence in Media

The lack of presence is absence, which is one of the most overused tropes in media.

Below is just a small sample of fictional characters with an absent father. It creates tension, drama and most importantly it’s relatable.

High Presence in Media

Fathers with High Presence are a lot less common, because to an outsider a highly present father is boring. So when the character is included, it usually comes with a comedic or tragic angle.

Presence as a question

Think of the most memorable conversation you ever had with someone.

Why was it memorable?

Two people connecting over something in a truly meaningful way.

You didn’t only pay attention.

You opened up to be affected by each other.

You were both present.

Imagine the same question is asked of your child:

“What was the most memorable conversation you ever had?”

Would they pick a memory of a conversation with you?

What is Presence?

Pope Francis said:

“We often hear that ours is a 'society without fathers.' In Western culture, the father figure is said to be symbolically absent."

The challenge of fatherhood today is a challenge of presence.

But it’s a concept so vague that even the Oxford Dictionary can only define it as “the fact or condition of being present”.

To gain a better understanding, we need to turn to theology with the help of Gabriel Marcel and his Availability Theory

He was a Catholic existentialist philosopher who defined presence as disponibilité (availability).

To be available to another person is to be fully present, open, treating them as a “Thou” not an “It”. To be unavailable is to be selfish, distracted, treating others as objects.

Marcel called this unavailability “the broken world” (le monde cassé): a world where people are reduced to functions, where relationships are transactional, where presence is impossible.

Marcel argued that when you are fully present to another person (truly available) you encounter what he called the “Absolute Thou”. As if God showed up in presence between people.

This led to his conclusion that full presence to another human is a form of communion with God.

This is why you can not only recognize presence but it’s also one of the most memorable human experience.

Presence as divine duty

The Hebrew word for presence is Panim (פנים) which also means face. This duality is not by coincidence. The Aaronic blessing in Numbers 6:24-262 talks about God turning His face toward you so you may be in His presence.

Presence means turning your face to another.

Ephesians 3:14-153 says that every family is derived from the Father. Paul makes a wordplay here as the Greek for family (patria) is derived from the Greek for father (pater).

According to the Cathecism4, for a child, parents are the first representatives of God.

In other words when you’re present, your child experiences God’s presence through you. When you’re absent, your child experiences God’s absence through you.

To turn your face away from your child is nothing less than denying their experience of God’s presence. Therefore being a present father is not merely a virtue but divine duty.

How to spot High Presence People

They don’t put their phone on the table

They’re behind on the news

They respond slowly

They seem slightly out of touch

They are never in a hurry

They are often silent

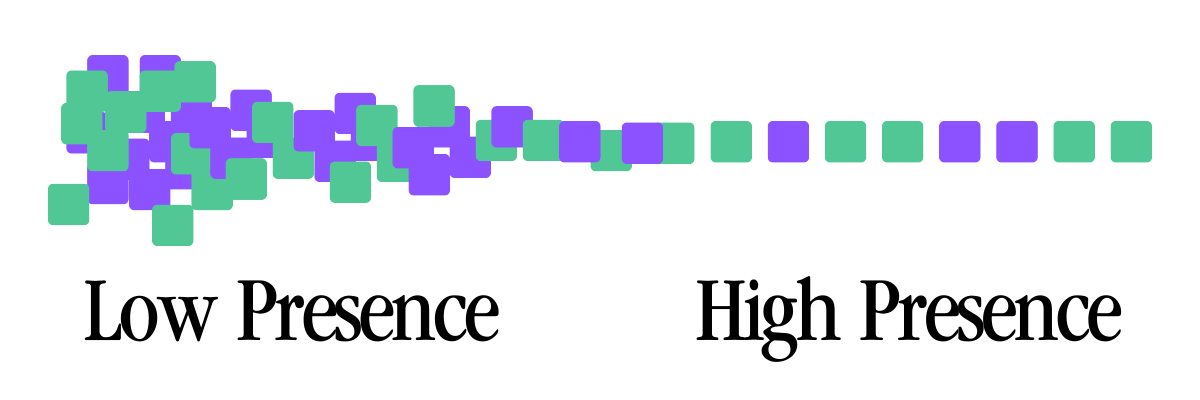

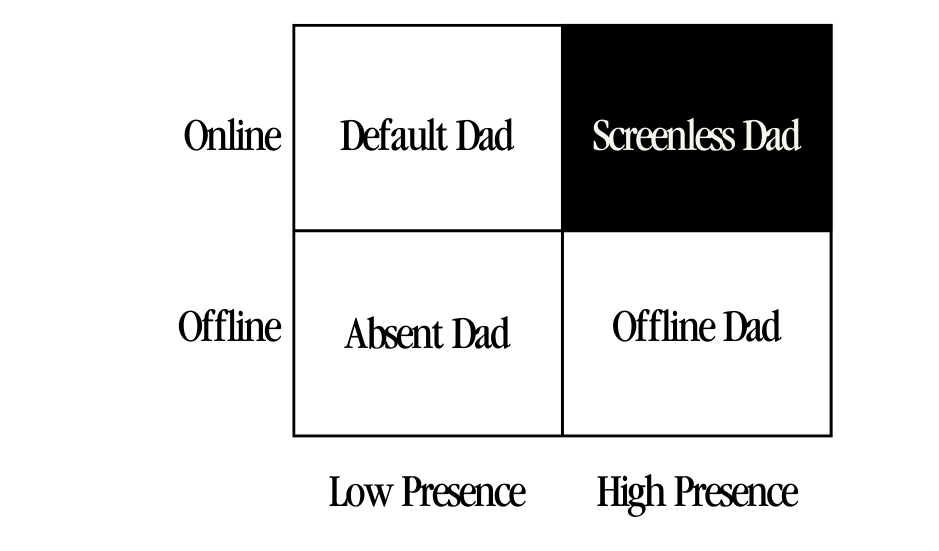

The Presence Spectrum

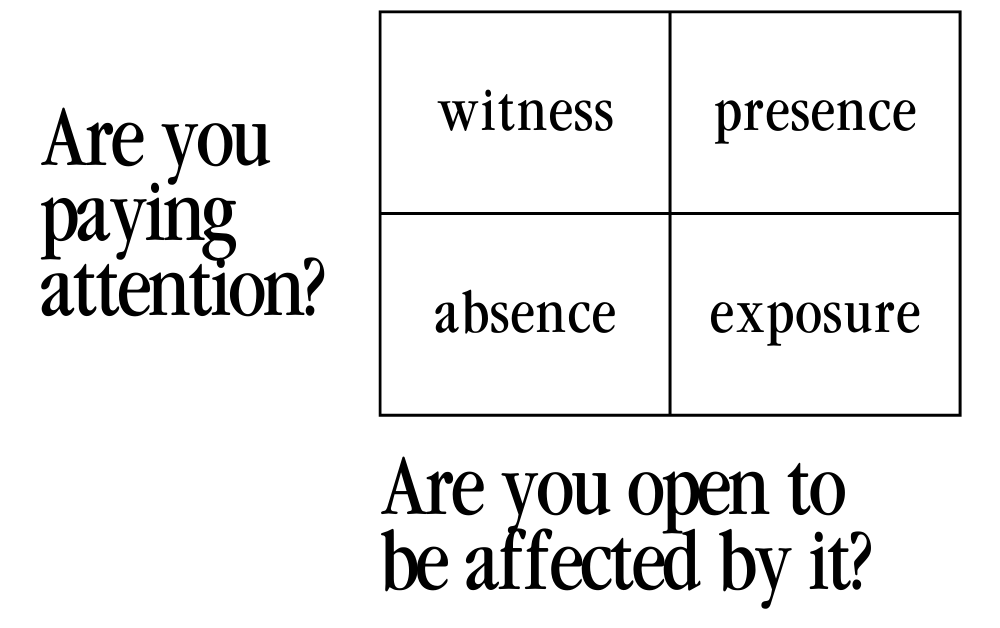

Presence is the product of two independent control networks5. The Central Executive Network manages your attention while the Salience Network detects what matters enough to be affected by it.

When both networks are aligned, a.k.a. you pay attention to the thing and let yourself be affected by the thing, you’re experiencing High Presence.

Witness: When you’re paying attention but your brain registers it as unimportant, you are only a witness. A bystander. You observe, monitor the events with no regard to their importance.

Exposure: When you’re not really paying attention yet you’re affected, you’re exposed. Passive doomscrolling, endless Netflix binges are when your brain is tricked into thinking it’s paying attention, but in reality you’re in a slightly hypnotic, zoned-out state.6 Your brain is pulled by a thousand strings and you don’t even notice.

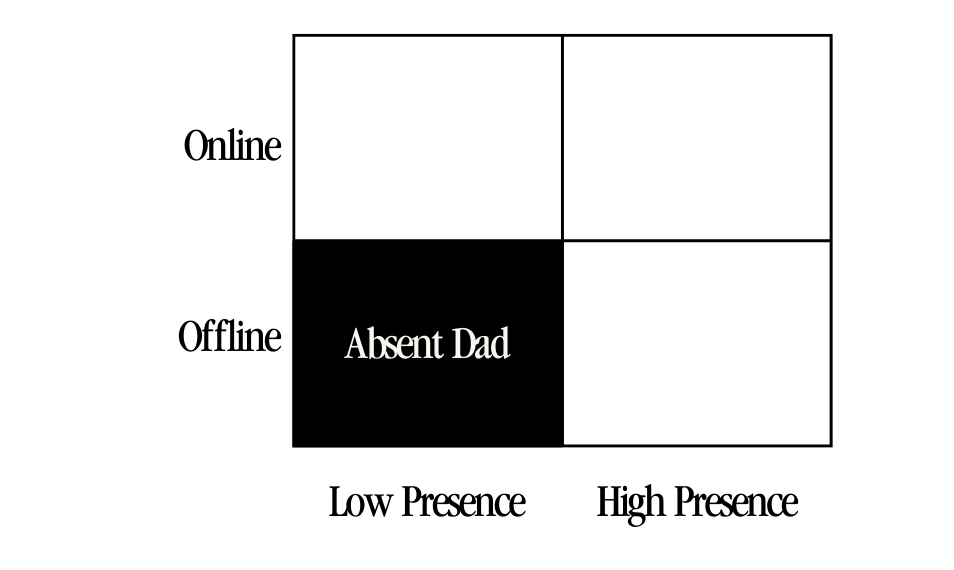

Absence: The total lack of attention and openness means the only thing that’s truly there may only be your body. Just because you’re physically in the room, you can be absent.

For the rest of this post I will treat anything that’s not High Presence as Low Presence.

The difference is whether your attention is a liability or an asset. High Presence means you deploy your attention with intent.

Low Presence means your attention is pulled by a thousand strings.

Are you present?

You might be wondering as I did:

Am I present? Would my daughter say I’m present?

The bad news: Low Presence is the default setting for most of us.

You inherited a brain evolved for a world of scarcity where any new information could mean survival. A rustle in the bushes might be a tiger. A new face on the horizon might be a threat. Your ancestors who ignored novel stimuli got eaten. The ones who paid attention to everything survived and reproduced.

Congratulations: You’re descended from the most distractible humans in history.

Then you put a device in your pocket that exploits that evolutionary wiring 1,000 times a day. A device engineered by the smartest minds at the richest companies in history, all focused on one goal: capturing your attention.

Every notification is designed to trigger your novelty-seeking brain. Every scroll reveals something new.

Tristan Harris, former Google design ethicist, explains it bluntly:

“Your phone is not designed to help you. It’s designed to extract attention from you. You are not the customer. You are the product.”

We all run on default settings unless we do something about it every day. It’s not your fault.

It’s just that we’re apes with iPhones.

The good news: You can engineer presence.

As countless examples show, becoming more present is possible. The most present parent in the world wasn’t born that way.

They engineered their environment.

They made choices.

Hard ones.

The goal of this essay is to do just that. Nudge you nearer towards being the parent your child would have their most memorable conversations with. To get you started with re-engineering your environment so it serves your family and not the other way around.

The essay is split into five parts:

Presence Software — Four lines about presence you can install in your brain today.

The Most Present Fathers — The story of possibly the three most present fathers.

The Absence Traps — The 5 most common absence traps parents find themselves stuck in and potential escape routes.

Which Dad are you? - The three archetypes of Dad behaviour when it comes to technology

Becoming Screenless — Practical techniques to start using presence today.

This essay is what I wish I read before holding my daughter for the first time, rather than writing half a year into fatherhood.

Part 1: Presence Software

People on the presence spectrum don’t passively download their relationship with technology from others.

However, many have independently installed four similar lines of software in their heads:

1. There’s no notification worth missing this

The human brain is an attention machine. If you train it to respond to every buzz, it will. If you train it to recognize what actually matters, it will do that instead.

When faced with the urge to check your phone during a moment with your child, ask yourself: “What notification could possibly be more important than this?”

Let’s think through the possibilities:

A work email? It will still be there in an hour. Your employer survived before Slack. They’ll survive while you’re at the playground.

A text from a friend? Real friends understand delayed responses. If they don’t, they’re not real friends.

Social media notification? Someone liked your post. Someone commented on your photo. Someone you barely know had a thought. None of this matters.

Breaking news? It’ll still be broken in an hour. And it probably doesn’t affect your actual life anyway.

The only notification that might be worth interrupting a moment with your child: An actual emergency. A true crisis. And how often does that actually happen? Once a year? Once a decade?

The average American checks their phone 352 times per day7. That’s once every 3 minutes of waking life. Of those 352 checks, approximately 351 are not emergencies.

Catherine Price, author of How to Break Up With Your Phone8, describes the irony:

“We keep our phones close because we’re afraid of missing something important. But by constantly checking, we guarantee we’ll miss the most important things: the moments actually happening in front of us.”

The first time my daughter Hanna looked into my eyes and smiled, I almost missed it.

What if I’d been looking at my screen instead? I would have missed the moment I’ll remember forever. For what? A meme? A news article? Someone’s vacation photos?

Emergencies are rare and scrolling is constant.

One deserves your attention, the other steals it.

2. There’s no perfect capture

The photo you took won’t capture the feeling. The video won’t recreate the moment. What preserves magic is experiencing it fully. Without a screen between you and the moment.

There’s a famous psychology study where researchers had people visit a museum9. One group could take photos, the other couldn’t. Later, researchers tested what both groups remembered.

The no-photo group remembered more, in detail.

The photo group relied on their cameras as external memory and their brains stopped encoding the experience. Scientists call this the “photo-taking impairment effect.” The act of taking photos actually reduces memory formation.

So when you’re documenting your most precious moments, you’re actually deleting them.

Susan Sontag wrote about this decades ago10, before phones had cameras:

“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power.”

She’s right. Photographing feels like capturing. But you’re not capturing, you’re trading.

Trading presence for documentation.

3. There are no algorithms for connection

Apple Photos will show you “Memories” from years past.

Facebook will remind you of posts from this day in history.

Google Photos will auto-create videos set to music.

These algorithms are designed to make you feel something. But they’re not your memories, they’re just data.

The real memories live in your brain. And real memories are formed when you’re actually present, not when you’re documenting.

Your child won’t remember if you got the perfect angle on their birthday cake. They’ll remember if you were laughing with them when they blew out the candles. They’ll remember if you were paying attention when they made their wish.

Algorithms can only simulate connection, not create it and kids know the difference.

Computer scientist Cal Newport puts it simply11:

“Solitude deprivation—a state in which you spend close to zero time alone with your own thoughts—decreases the capacity for connection. You can’t be fully present with others if you’ve never learned to be present with yourself.”

4. You’re always present for something

Right now, in this moment, you’re reading. You’re present with these words. In a moment, you’ll be somewhere else. Maybe you’ll be with your child. Maybe you’ll be scrolling.

The choice is always: What will I be present for?

Because you’re always present for something. Every moment of attention is spent somewhere. The question is whether you’re spending it on a screen or on your life.

Your children will remember whether you were present or absent. They’re building their understanding of love, attention, and value based on how you show up.

Every scrolling session is teaching them something.

Every moment of presence is teaching them something else.

Part 2: The Most Present Fathers

The three most common excuses men make for not being present are being busy, powerless or late. In this part I will tell the story of three men to prove these are all lies we tell ourselves.

#1 You’re never too busy to be present

It’s September 1901. Theodore Roosevelt has just become President of the United States at 42, the youngest in American history. He’s stepping into one of the most demanding periods of the executive branch: trust-busting the railroad monopolies, managing the Panama Canal construction, navigating international crises that would reshape America’s position in the world.

He’s also raising six children.

By every measure Theodore Roosevelt should have been an absent father. He had legitimate excuses. He had the most demanding job on Earth with cabinet meetings, state dinners or foreign delegations.

Instead, he became one of the most present fathers in history.

You Must Not Keep a Small Boy Waiting

One afternoon, the President was in his office discussing matters of state with an important visitor when his youngest son Quentin appeared and announced: “It’s four o’clock, Father.”

Roosevelt checked his watch.

“So it is.”

Then he promptly terminated the meeting, telling his guest: “I promised the boys I would play with them at four o’clock… and you know you must not keep a small boy waiting.”

This wasn’t a one-time performance. Historian David McCullough described the pattern12:

“Sometimes cabinet meetings had to be called off because the children were banging around upstairs on stilts or whatever... And the father would sometimes be late for state banquets because he was upstairs either reading the bedtime story or telling them a tall tale or having a good all-out pillow fight.”

The White House Gang

The Roosevelt children didn’t just live in the White House.

Quentin, the youngest, led a group of boys known as the “White House Gang”13 that included Charlie Taft (son of the Secretary of War and future President), Roswell Pinckney (son of the White House steward), and friends from the local Force School. President Roosevelt, an honorary Gang member, would often curtail official business to join the boys for hide-and-go-seek and other spirited activities. TR frequently challenged the lads to obstacle races in the White House’s hallways.

Go Enliven Their Tedium

One day, during a meeting with the Attorney General, Roosevelt’s son Quentin entered the room and placed three snakes in his father’s lap. Roosevelt is reported to have calmly stated to his son, “Hadn’t you better go into the next room? Some congressmen are waiting there and the snakes might enliven their tedium.”14

Read that again. The President of the United States, in a meeting with the nation’s top law enforcement official, received a lapful of snakes from his son—and his response was to redirect the boy toward the congressmen waiting next door.

The hierarchy was clear: his children could interrupt anything.

Theodore Roosevelt was simultaneously one of the busiest and most present fathers in American history.

This destroys the excuse that presence requires having less to do.

He didn’t have less on his plate than you do. He had more. Immeasurably more.

He was running a nation during one of its most transformative periods.

And he still let his kids interrupt cabinet meetings. Still scheduled pillow fights. Still sent hand-drawn letters from hunting camps in Africa. Still ended meetings because “you must not keep a small boy waiting.”

The next time you think you’re too busy to be present, remember that the President of the United States let his son put snakes in his lap during a meeting with the Attorney General.

Your Slack messages can wait.

#2 You must engineer your presence

There’s a comforting lie people tell themselves about Fred Rogers: that he was simply born that way.

That his preternatural calm, his ability to make children feel seen through a television screen, his capacity to hold silence while the whole world rushed…these were gifts.

Things he had and we don’t.

This is the lie that lets us off the hook.

The truth is more uncomfortable and more useful:

Fred Rogers spent thirty years engineering his presence.

Every pause, every word, every ritual was the product of deliberate practice, deep study, and systems he built to protect his attention.

The Architect Behind the Neighborhood

In the 1950s, a young Fred Rogers enrolled at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary while working on a children’s television show. For a counseling course, he was assigned to work under a child psychologist named Margaret McFarland at the Arsenal Family and Children’s Center.

McFarland had co-founded the Arsenal Center as a nursery school and counseling center with pediatrician Benjamin Spock and psychologist Erik Erikson.

Erik Erikson said of McFarland: “Margaret McFarland knew more than anyone in this world about families with young children.”

After Rogers’ course ended, he didn’t stop meeting with her. For 30-some years, until her death at the age of 83 in 1988, Rogers and McFarland would meet weekly to discuss children, upcoming scripts, props for the show, or song lyrics. They often talked daily.15

For three decades, Rogers submitted every script, every song lyric, every prop choice to rigorous psychological review. This wasn’t natural talent—this was engineering.

So much of Rogers’ thinking about and appreciation for children was shaped and informed by McFarland’s work (actually by her very being) that to know and love Mister Rogers is to know and love Margaret McFarland.

Attitudes Aren’t Taught, They’re Caught

McFarland’s philosophy contained a radical insight that shaped everything Rogers did.

She believed that a teacher did not so much teach a specific attitude to a student, but that the child “caught” a certain attitude toward a subject based on the teacher’s enthusiasm and commitment to the material.

This insight was captured in one famous instruction. When McFarland wanted to expose children at the Arsenal Center to sculpting, she instructed him not to teach the children how to sculpt, but instead to just “love clay in front of the children.”

And that’s what he did. He came once a week for a whole term, sat with the four- and five-year-olds as they played, and he “loved” his clay in front of them16.

Rogers applied this same principle to presence itself. He didn’t teach children about attention. He practiced attention in front of them. Every episode was a masterclass in what focused, unhurried presence looked like—not explained, but demonstrated.

Presence is an engineering problem

86% of parents try to establish rules over screentime but only 19% can stick to it consistently.17

We know now that this is a result of addiction by design.

Mindset shifts and willpower are not enough to cultivate presence. It’s an engineering problem and engineering problems can be solved.

You’re not powerless in your fight against screen addiction. You’ve been trying to use the wrong tools.

Presence doesn’t happen on its own, you must engineer your environment cultivate it.

#3 You are never too late to be present

Kobe Bryant lived in Orange County. Peaceful, good schools, nice people. The kind of place you raise kids.

The Staples Center was 49 miles away. In Los Angeles traffic, that commute could consume two to three hours, each way.

He was, by any measure, one of the most dedicated athletes in the history of professional sports.

He also had four daughters whose school plays and practices and games and bedtimes kept happening whether he was available or not.

Just like Theodore Roosevelt, Kobe had the perfect excuse to be too busy to be present. Most men in his position would have outsourced fatherhood. They would have hired nannies and drivers and told themselves that providing wealth was providing presence. They would have shown up for the big moments and missed the daily ones thinking it’s okay.

But Kobe realized it was not okay.

“I was sitting in traffic and I wound up missing a school play because I was sitting in traffic, and this thing just kept mounting, and I had to figure out a way where I could still train and focus on the craft, but still not compromise family time,” Bryant said.18

For a man who approached basketball with obsessive precision, who studied every opponent’s tendencies and refined every movement until it was perfect, a broken system was intolerable.

So he did what engineers do. He found a different solution.

“And so that’s when I looked into helicopters and being able to get down and back in 15 minutes. And that’s when it started.”

It Takes a King to Make a Princess

In 2017, Kobe addressed the teasing he received about having all daughters. His friends would joke: “Guys keep teasing me,” he told Extra.

“My friends say, ‘It takes a real man to make a boy.’ I’m like, ‘Dude, it takes a king to make a princess… get in line.’”19

When ESPN anchor Elle Duncan met him backstage at an event in 2018, she was eight months pregnant. Before she could even ask for a photo, Bryant zeroed in on her belly.

“’How are you? How close are you? What are you having?’ ‘A girl,’ I said, and he then high-fived me.”20

Duncan asked for advice on raising girls. Bryant’s response:

“Just be grateful that you’ve been given that gift because girls are amazing.”

Then Duncan asked the question everyone asked him. His wife Vanessa wanted to try for a boy. What if it was another girl? Four girls, could you imagine?

“Without hesitation, he said ‘I would have five more girls if I could. I’m a girl dad.’”

That phrase ”girl dad” would become a movement. After his death, it trended worldwide. Fathers everywhere claimed the identity.

As a girl dad myself, this speaks really close to my heart.

The Hands-On Father

At Kobe’s Hall of Fame induction, his widow Vanessa revealed just how present he was in daily family life:

“His most cherished accomplishment was being the very best girl dad,” she said. Vanessa then gave the world a glimpse into the kind of husband and father he was to their four daughters. After Kobe would wake up at 4 a.m. for his workouts, he’d make sure he was home in time to give Vanessa a kiss when she woke up in the morning. He’d then drop his daughters off at school, go to Lakers practice and be back in time to pick them up from school whenever he could.21

She added that Kobe always tried his best to never miss a birthday or his daughters’ dance recitals, school awards shows or show-and-tells.

At the public memorial following their deaths, Vanessa shared more:

“When Kobe was still playing, I used to show up an hour early to be the first in line to pick up Natalia and Gianna from school and I told him he couldn’t drop the ball once he took over. He was late one time and we most definitely let him know that I was never late,” Vanessa continued. “So he showed up one hour and 20 minutes early after that.”

He was late once. The family let him know. He overcompensated by showing up eighty minutes early.

This was the Mamba Mentality applied to fatherhood. Failure was unacceptable. Improvement was mandatory.

Somehow finding ways

The man famous for his relentless self-focus, for demanding the ball in clutch moments, for the almost pathological drive to be the best—that man found something more important than himself.

“His most cherished accomplishment was being the very best girl dad,” Vanessa said at the Basketball Hall of Fame ceremony. “I want to thank him for somehow finding ways to dedicate time to not only being an incredible athlete, a visionary, entrepreneur, and storyteller but for also being an amazing family man.”22

“Somehow finding ways.”

That’s the key phrase. It wasn’t luck. It wasn’t natural talent. It was engineering. It was applying the same obsessive problem-solving that made him a champion to the problem of presence.

It wasn’t too late for Kobe to make the change even if he tragically only got a few years.

Don’t obsess about whether you’re late. You’re not.

Obsess about being more present, starting today.

Part 3: Absence Traps

The Presence Spectrum revealed four types of presence: High Presence, Witness, Exposure, and Absence. Each absence trap pulls you toward a different corner of the matrix, away from the top-right quadrant where real connection lives.

Understanding which quadrant you’re stuck in helps you find the escape route.

Absence traps will push you lower on the Presence Spectrum towards Absence by breaking one or both controls:

Your Central Executive Network loses control of attention → you stop choosing what to focus on

Your Salience Network gets hijacked → you stop being affected by what actually matters

And it’s everywhere.

Low Presence is scrolling while your child tells you about their day, nodding without hearing a word.

Low Presence is checking email during bedtime stories “just in case.”

Low Presence is being physically in the room but mentally in your phone. Your body a placeholder for a person who isn’t really there.

These traps act like a prison of the mind. Unlike a real prison, there are no physical guards or walls.

If you’re stuck in an absence trap, you’re both the guard and the prisoner. The prison exists purely in how you relate to your device, which is by default a product of your environment and not of choice.

Countless absence traps exist. I’ve listed the five most common ones, which quadrant they pull you toward, and potential escape routes.

1. The Just-One-More Trap

Quadrant: Exposure

If your child asked you to play and you were stuck in the just-one-more trap, here’s how it would go:

Child: Dad, come play with me!

You: Just one more email... [5 minutes later]

Child: Dad?

You: Just one more scroll... [10 minutes later]

Child: ...Dad?

You: Just one more video... [Child gives up, plays alone]

The just-one-more trap is pure Exposure. Your Salience Network is being pulled by a thousand strings. Each video, each post, each notification triggers that ancient “this might be important” reflex. But your Central Executive Network has checked out. You’re not choosing to watch. You’re being watched.

This trap exploits a quirk of human psychology: We’re terrible at predicting how long “just one more” will take. Psychologists call this the “planning fallacy.” We chronically underestimate duration.

But there’s something worse: The scroll is designed to be infinite. There is no natural stopping point. Every video leads to another. Every post suggests ten more. The algorithms know exactly how to keep you in the Exposure quadrant forever.

Affected but not attending, pulled but not choosing.

You’re not battling your own will. You’re battling teams of engineers optimizing for engagement. It’s not a fair fight.

Escape Route: Create artificial stopping points.

Since digital content has no natural end, you must create artificial ends that force your Central Executive Network back online:

Physical timer: A visual timer that dings when phone time ends

App limits: Hard limits that lock you out (not the kind you can bypass)

Environmental barriers: Phone in another room removes the option entirely

Better yet, design your environment so “one more” isn’t an option. If your phone is in the car, you can’t check “just one more” thing. You move from Exposure to the present moment by removing the strings entirely.

2. The Documentation Trap

Quadrant: Witness

If your child was having a magical moment and you were stuck in the documentation trap, here’s how it would go:

Child: Look at the butterfly, Daddy!

You: Hold on, let me get my phone out...

Child: It’s flying away!

You: Wait, I almost have the shot...

Child: It’s gone.

You: Well, I got the tree it landed on.

[Posts photo of empty tree. Gets 12 likes. Neither remembers the butterfly.]

The documentation trap pulls you into the Witness quadrant. Your Central Executive Network is engaged.

You’re paying attention, framing the shot, adjusting the focus. But your Salience Network registers it all as data to capture, not a moment to feel.

You observe without being affected.

The logic seems sound: “I’m filming this for the memories! So we can look back on it! So we’ll have it forever!”

But the person documenting is not the person experiencing. The camera creates a barrier (physical and psychological) between you and the moment.

The camera becomes a substitute for openness, not a supplement to it. You’re technically attending, but you’ve closed yourself off from being moved.

Escape Route: Capture boring moments.

To move from Witness to High Presence, you need to sync with Salience Network to let the moment affect you:

No photos when things are happening

Document only when nothing is happening

Your child won’t remember if you got the photo. They’ll remember if you saw their face when the butterfly landed. That requires both attention and openness.

Ask yourself, do you really need to take that photo?

When my daughter was born, the doctor asked me where my phone was so he could take a photo of us. I told him I didn’t want the moment to be photographed. I wanted to experience it fully. Take it in.

He was visibly confused. He identified with these screen-dependent habits so much that he misunderstood my presence as lack of care.

Then once everything settled down, we did take some photos.

There are loads of photos on my phone I regret taking instead of being present. I can’t think of one I regret not taking.

3. The Productivity Trap

Quadrant: Rapid oscillation between Absence and Exposure

If you were trying to be “efficient” with your child, here’s how the productivity trap would sound:

“I’m being smart with my time! I can watch the kids AND catch up on emails! I’m multitasking!”

No, you’re not.

On the Presence Spectrum, you’re rapidly bouncing between quadrants: momentary Exposure to the phone, then momentary Absence from your child, then back again.

Neither your Central Executive Network nor your Salience Network can stabilize. You never land in High Presence with either task.

Research is overwhelming: Humans don’t multitask. We task-switch. And every switch has a cognitive cost. Studies show it takes an average of 23 minutes to fully regain focus after a distraction.

When you’re “watching” your kid while checking email, you’re doing both poorly. You’re not being productive with email—you’re sending typo-riddled half-thoughts. And you’re not being present with your child—you’re being a distracted ghost oscillating between Absence and Exposure without ever landing in presence.

Clifford Nass, Stanford professor who studied multitasking for decades, found23:

“People who multitask all the time can’t filter out irrelevancy, can’t manage working memory, and are chronically distracted. They’re worse at every cognitive task we could measure—including multitasking itself.”

Escape Route: Batch, don’t blend.

High Presence requires both networks aligned on the same target. You can’t split them and expect presence with either.

Handle email when you handle email. Be with your kid when you’re with your kid. Create clear boundaries between modes:

Phone hour: 7-8am, before kids wake

Kid time: 8am-bedtime, phone in foyer

Phone hour: After kids in bed

Your child isn’t interrupting your work. Your phone is interrupting your parenting. Pick one quadrant and commit—ideally the top-right one, with your child.

4. The FOMO Trap

Quadrant: Exposure (to phantom stimuli)

If you were experiencing FOMO while with your child, here’s the internal monologue:

“What if something important is happening?

What if I miss big news?

What if someone needs me?

What if there’s an emergency?

What if everyone’s talking about something and I don’t know?”

The FOMO trap is a particularly insidious form of Exposure. Your Salience Network is being hijacked—not by content on your screen, but by imagined content you might be missing. You’re being affected by notifications that haven’t even happened. Your Central Executive Network can’t focus on your child because your Salience Network keeps screaming about phantom threats.

You are missing something.

You’re missing your child’s childhood while worrying about missing a tweet.

Let’s be honest about what you might miss by not checking your phone:

A news story you’ll forget in 24 hours

A social media controversy you have zero control over

A meme that will be replaced by another meme tomorrow

A work email that can wait until tomorrow

Now let’s be honest about what you might miss by checking your phone:

Your child’s face when they figure something out

The random hug they were about to give you

The question they were building courage to ask

The window of connection that closes when you look away

Which loss is worse?

Escape Route: Reframe FOMO as JOMO—Joy Of Missing Out.

To escape, you need to recalibrate your Salience Network. Train it to recognize what actually matters:

Every notification you miss while playing with your child is a victory, not a loss. The news will still be there. The controversy will exist without your participation. The meme will be archived.

Your child’s giggle at this exact moment will not.

When you feel FOMO pulling you toward Exposure, name it: “My Salience Network is being hijacked by phantom importance.” Then redirect both networks to what’s actually in front of you.

5. The Someday Trap

Quadrant: Absence (temporal)

If you were stuck in the someday trap, here’s how your mind would rationalize:

“I’ll be more present... someday. When work calms down. When this project ends. When the kids are older and more interesting. When I’m less stressed. I’ll be the present parent I want to be…just not today.”

The someday trap is pure Absence but displaced in time. Your Central Executive Network isn’t engaged with now because it’s planning for later. Your Salience Network doesn’t register this moment as important because you’ve mentally tagged “someday” as when things will matter.

Both networks are offline for the present moment. Your body is a placeholder.

The someday trap is the deadliest because it feels reasonable. You’re not saying “never.” You’re saying “later.” Later feels responsible.

But later never comes. There’s always another project. Always another stressor. Always a reason why today isn’t the right day to move into the High Presence quadrant.

And meanwhile, your children are growing. They’re only four once. They’re only seven once. They’re only ten once.

The comedian Nate Bargatze has a bit about this:

“My daughter’s only going to be four once. She’s never going to be four again. I want to be there for that. I mean, she was only three once too, and I pretty much missed it because of my phone.”

Writer James Clear puts it mathematically:

“If your child is 5 years old, you’ve already spent 90% of the time you’ll ever spend with them. The vast majority of your time together is already behind you.”

Escape Route: The math is brutal. Face it.

Calculate it yourself:

How many hours per week do you spend with your child?

How many of those hours are you actually in High Presence vs. the other three quadrants?

How many years until they leave for college or move out?

Multiply. That’s your remaining presence budget. There is no “someday”—there’s only a finite number of hours left.

Someday is now. Today is the day. There is no better time to align both networks on what actually matters.

Each trap pulls you toward a different corner of the Presence Spectrum. But they all share the same escape route: recognizing which network has been compromised, and deliberately bringing both back online—attention AND openness—pointed at the person in front of you.

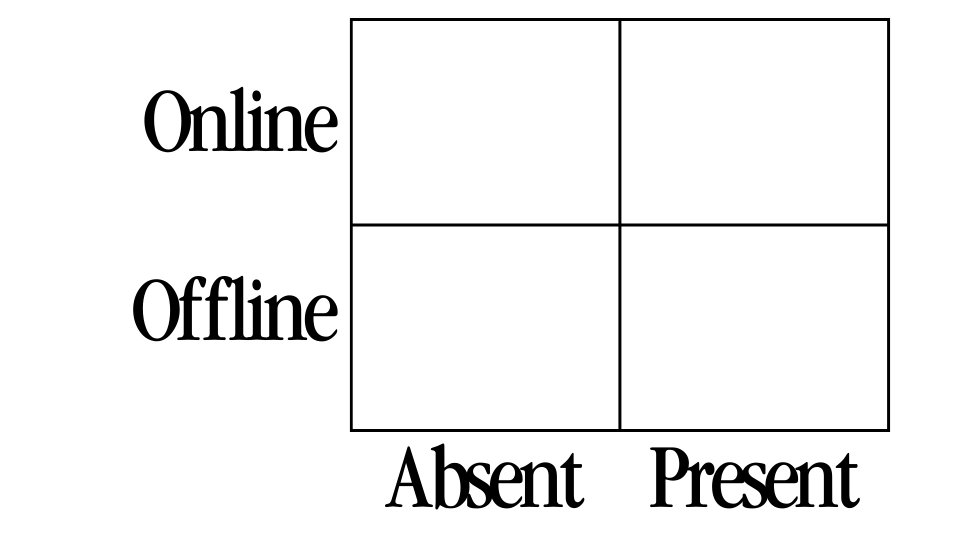

Part 4: Digital Dads

Most of these traps have nothing to do with your devices, smartphones, social media or AI. They have been around for ages.

Yet it’s easy to become a purpose-driven Luddite and think that technology is breaking us.

But that’s not true. Technology is built to exploit what’s already in us. So while the issue remains, depending on your relationship to technology, the question of Presence gets another dimension:

We already established that we’re basically apes with iPhones.

Our brain runs software that manages our presence but the software is broken.

According to a 2002 study24 (before social media!) for every clinic-referred girl with ADHD diagnosis, there are 10 boys.

When men become fathers, this software decides what Dad Mode gets loaded, but it has a template that’s expired long ago.

The human brain is incompatible with the dense, information rich world we live in. Bluntly put, as Dr David D Gilmore said in his 1991 book Manhood in the Making25, men are built to provide, protect and procreate.

This is the template. To reconcile our urge to provide, protect and procreate with the complexity of our world, most men had a simple solution for this for hundreds of years:

Checking out.

The Absent Dad

It’s not new. Our fathers did it too.

The Absent Dad existed long before the iPhone. He’s the original disengaged father, without algorithms.

The Dad who isn’t online but isn’t present either.

That’s why it’s so prevalent in the media.

That’s why it’s so relatable.

This is the dad in the garage “fixing something” for six hours on a Saturday. The dad at the pub after work. The dad behind the newspaper at breakfast, grunting responses. The dad who was physically in the room but mentally on another planet.

As poet Robert Bly wrote in his 1990 book Iron John:

“The father’s absence has created a famine in the sons.”

Bly was talking about the industrial revolution pulling fathers out of the home and into factories. Sons stopped learning from fathers. The bond broke over a century ago.

Before the smartphone, there was the television. Before the television, there was the radio. Before the radio, there was the newspaper. Before the newspaper, there was the bottle. Men have always found ways to check out.

The Absent Dad doesn’t need TikTok to disappear. He has the shed. The golf course. The “I need to clear my head” drive that takes three hours. The fishing trips. The overtime that wasn’t mandatory. The business dinners that could have been emails.

This is why saying “I’m going to mow the lawn” makes wives furious around the world26. It’s not about the lawn. It’s the checking out.

His body is offline but his mind is somewhere else entirely.

If you’re a millennial, you probably have an Absent Dad story. Maybe it’s the football match he missed. The school play he forgot. The conversation you needed but never got. The hug that felt awkward because there weren’t enough of them.

The Absent Dad checked out because post-war masculinity told him that’s what men do.

Provide money, stay stoic, keep emotions at arm’s length. Feelings were for women. His father wasn’t present, so why would he be?

As therapist Terry Real writes in I Don’t Want to Talk About It:

“Men are taught to be relationally illiterate. We are raised to be strangers to our own hearts.”

The Absent Dad isn’t evil. He was following a broken script handed down through generations. A script that said showing up emotionally was weakness.

There’s one thing that makes him different from you and I. At least he had an excuse. He didn’t know better. The culture didn’t give him the tools.

You don’t have that excuse.

You know that presence matters. You know that your kids need you emotionally, not just financially. The information is everywhere.

And yet.

Many of us swore we’d be different. We’d be present. We’d be there.

Then we got handed a supercomputer connected to infinite content and our brain lit up like a Christmas tree.

The Absent Dad evolved. He got an upgrade.

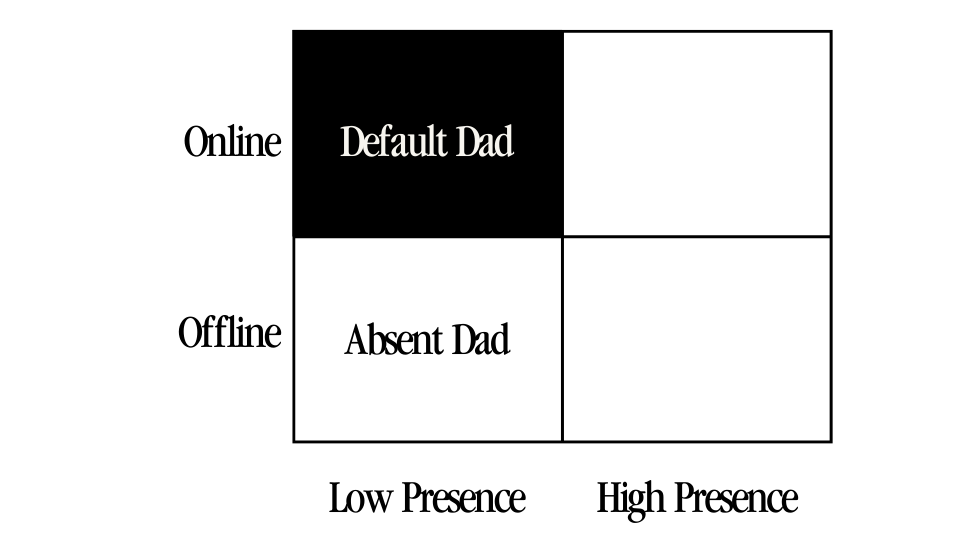

The Default Dad

According to a study, UK adults spend 76% of their awake time online.27

This is not by choice.

Providing for our families is almost entirely digital for the most of us. And that’s when the problems begin.

Because as the infamous Opal advertisement said:

“This is not an iPhone. This is a $3 trillion military-grade lethal weapon aimed straight at your brainstem."

So instead of providing for your family, you’re watching a Dutch guy in the Alps renovating a stone house at 1am.

But it’s not just about money. Our support systems got crushed too.

Humans were made for alloparenting28. For example, Efe infants have 14 alloparents a day by the time they are 18 weeks old, and are passed between caregivers eight times an hour.

Raising a family was never supposed to be just Mom and Dad.

It really does take a village.

So we are trying to be present in a hostile environment. Our urge to provide is being carpet bombed by digital crack while we are supposed to literally do the work of 7 people at home.

You don’t check out because you don’t know better. You check out because your nervous system gives up. The result is the same.

Enter Default Dad. Absent Dad with wifi and anxiety.

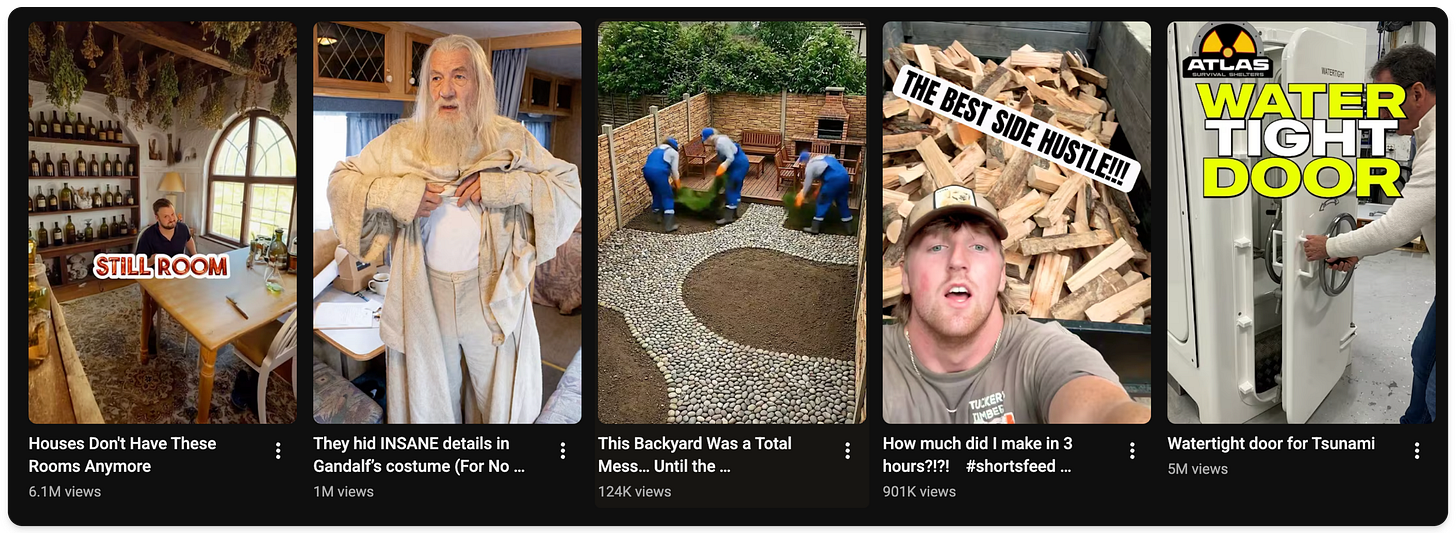

A highly curated Youtube feed of nerdy, DIY, business, fitness and prepper content as a result of months of doomscrolling on the toilet.

You do it. I do it. We all do it.

If you work in tech, it’s even worse, because you know exactly how this extraction machine works but you’re defenseless against it.

Your brain is fried and your default response is to fry it even more.

This is why you sit in the car for 10 minutes before arriving home.

This is why waking up before everyone else early in the morning feels therapeutic.

This is why you’re surprised that you have guests this weekend even though your wife told you six times.

And sadly for many men this is why the divorce came out of nowhere.

The Default Dad is passive, unaware. Life passes by.

Most men use work and exhaustion as an excuse to be Default Dad.

Some realize this and try turning their phone off.

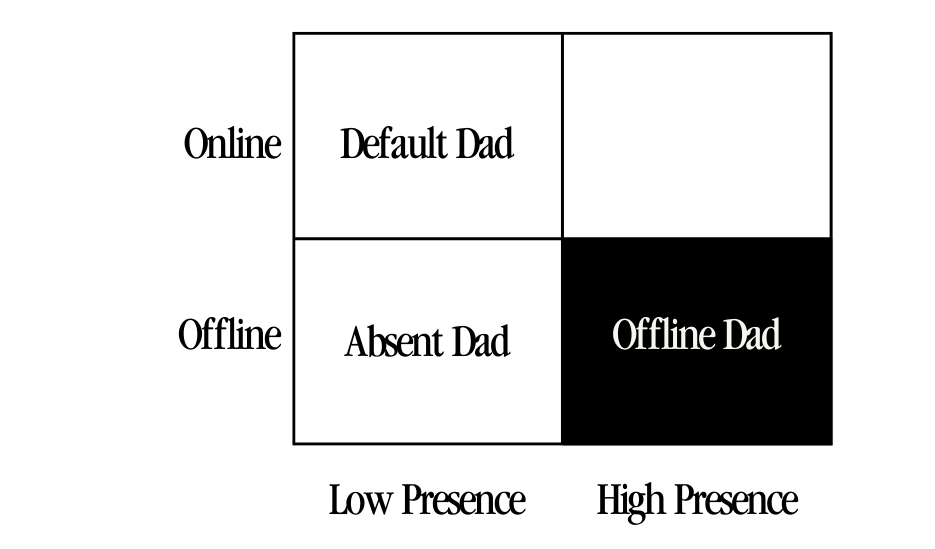

The Offline Dad

Ever since the Anxious Generation29 was published in 2024, millions of parents started ditching their smartphones and iPads.

Overwhelmed Default Dads having an AHA! moment and going offline.

They weren’t the first ones.

In 2010, a journalist asked Steve Jobs whether his kids loved the iPad30.

Jobs replied:

“They haven’t used it. We limit how much technology our kids use at home.”

The journalist was stunned. The CEO of Apple, the man selling these devices to every family in America was protecting his own family from them?

Jobs wasn’t alone. Chris Anderson, former editor of Wired and CEO of a drone company, has strict screen limits for his five children31.

“My kids accuse me and my wife of being fascists,” he told the New York Times. “They say none of their friends have the same rules. That’s because we have seen the dangers of technology firsthand.”

The architects of the attention economy knew the blueprint well enough to protect their own families from it. Drug dealers don’t get high on their own supply.

The term “screen free parenting” has become widely known with many influencers popping up offering solutions. Today millions of parents are trying to follow suit going offline as much as possible.

Millennials trying to recreate their own childhood and “raise 90s kids” is the popular, scaled up version of limited screentime. This includes parents buying VHS players and bathing in nostalgia as they feel that’s how to have a childhood the right way as an antidote to being chronically online32.

This is the life of the Offline Dad.

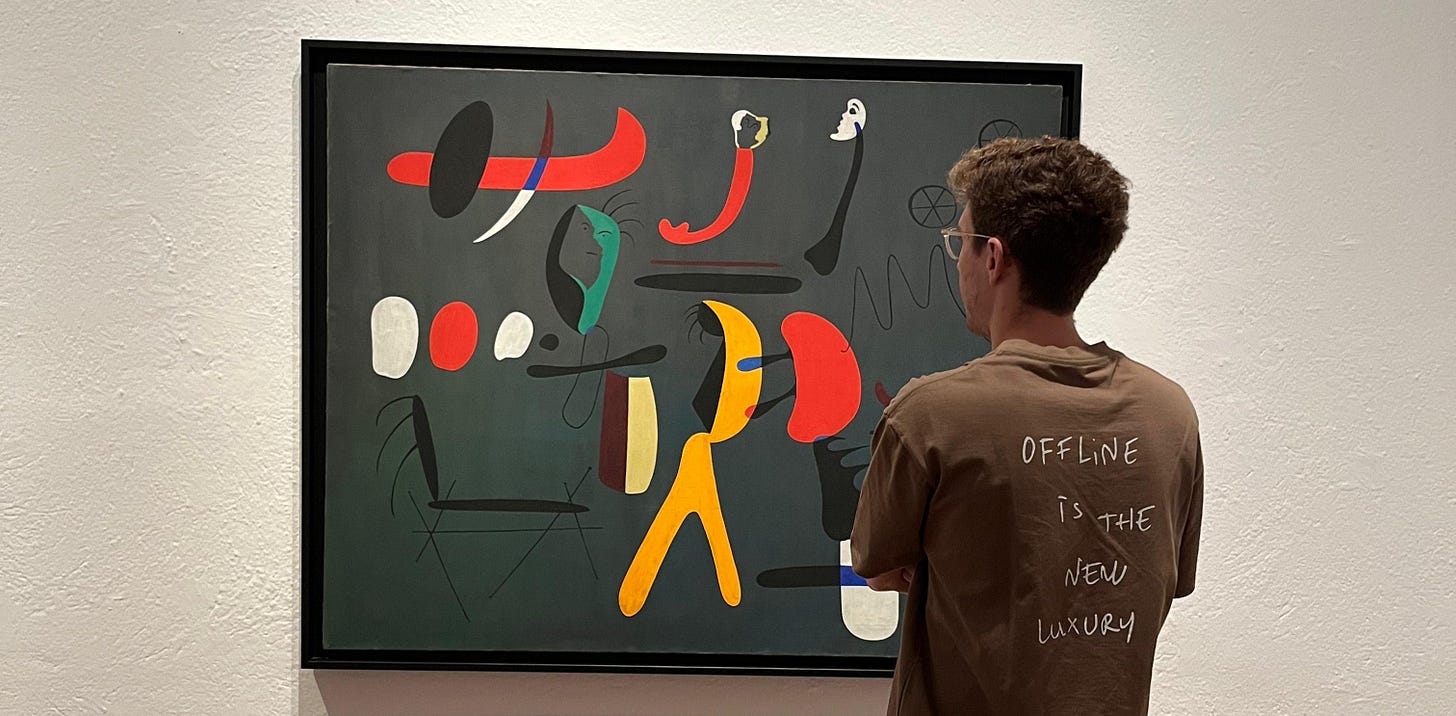

However this approach ignores two truths about being offline:

Offline is the new luxury.

A VPRO documentary from 6 years ago predicted that being offline is becoming the new luxury.

Retirement now means you don’t have to be online, that you can afford to live without social media.

The above examples are some of the wealthiest, most affluent people on the planet.

They can afford to go offline. You cannot.

This means that you will always be in that liminal space where you’re trying to not use tech but have to and you will ultimately fail. Then the hypocrisy will eat you for breakfast.

Offline parents raise digital illiterates.

You may shield your children from screens but they will become adults with zero coping mechanisms when exposed and they will be exposed. Our children will inherit a world with screens.

Opting out of digital literacy in 2026 is like opting out of literacy in 1926. You can do it, but you're consigning your kids to a narrower, more harmful world unless you deliberately compensate…and most don't.

The Offline Dad is just as passive as the Default Dad. He may be aware of the problem but buries his head in the sand.

You are more present, your kids are more present, but at the expense of their future.

There’s another layer of this though.

You can’t simply opt out from using digital services and products, but you also can’t cherry-pick which products you’ll use.

So your home becomes offline while you work online and you convince yourself that you’ll stay away from the addictive bits of the internet using…sheer power of will?

It’s not enough. If it was, drug addicts could go clean cold turkey without help. It may happen but it’s rare as a duck in tutu.

If you work in tech, then the Offline Dad might be an aspiration but you know it’s not realistic.

The Screenless Dad

Making your kids go offline while you’re secretly doomscrolling on the toilet is not only hypocritical, it also doesn’t work.

As the late Hungarian psychologist, Dr Tamas Vekerdy said33:

There is no such thing as upbringing. There’s only more or less effective coexistence with children.

Your children won’t learn your rules you make for them. They will model the ones you yourself follow. That’s why “loving the clay” worked.

This is why “rules for thee but not for me” don’t work.

You need to become present while connected in a healthy way so your children can model that.

This is hard. If your smartphone was a chemical compound, you’d need to learn how to handle it with care with proper disinfectation protocols and hazmat suits.

And things are getting worse with AI.

ChatGPT is the new TikTok in terms of how harmful it is to kids. Its idiotic sycophancy is frying the brains of our kids, our parents and so many otherwise smart people.

Australia has banned social media under the age of 16 in 2025.34 The UK is now considering following suit and we may see a widespread adoption of some regulation over the next 3-5 years in most Western countries.

While this is great news for concerned parents, don’t forget that Facebook was founded in 2004.

21 years passed before regulators woke up.

ChatGPT was launched in 2022. Do the math.

The development of the prefrontal cortex ends by the age of 25. For my daughter Hanna, this will be in the year 2050.

I need to prepare her for that life, not this. The world will be an increasingly hostile place for young people over the next few decades.

Which means I need to engineer our environment that allows healthy coexistence with technology, since going Amish is not an option.

This is the life of the Screenless Dad.

Living online while screenless.

Not buying an old Nokia 3310 and pretending it’s 1999, but reinventing your relationship with technology.

Because the relationship you have with tech today is something you never agreed to. So let’s renegotiate.

Part 5: Going Screenless

One of my clients, who shares this sentiment, said to me:

“Every day is a series of sessions where you’re thinking, speaking and doing things based on a specific intent.”

Some of those sessions are triggered by you. Some are triggered by others. And in between is the battleground.

The human-to-web interface

Screens aren’t the problem.

But screens are the only robust human-to-web interface we have.

The internet runs the world. Banking, communication, work, healthcare, education…it all flows through the web. And the only way humans can reliably access the web is through screens.

That’s not going to change anytime soon.

What HAS changed is that this interface (our only gateway to modern life) has been systematically weaponized against us.

Every pixel is optimized to extract attention.

Every notification is tuned to trigger your dopamine system.

Every scroll is infinite by design.

You’re not fighting screens.

You’re fighting teams of brilliant engineers at the richest companies in history, all focused on one goal: keeping you looking at the glass rectangle in your hand.

This is why willpower fails.

This is why “just put the phone down” doesn’t work.

This is why 86% of parents set screen time rules and only 19% can enforce them.

You’re bringing a knife to a drone fight.

Live with intent

Your weapon against absence is intent.

The Screenless Dad doesn’t avoid screens entirely. That’s impossible for most of us. Instead, he creates a scaffolding that ensures every screen interaction is intentional.

The question isn’t “how do I use screens less?”

The question is:

“How do I reduce my need for screens?”

When you analyze your screen time through this lens, you’ll find that most of your phone pickups aren’t intentional at all. They’re reflexive. Habitual. Extracted.

So here’s the idea: if you only do one thing as a result of reading this essay, do this:

Turn off all notifications on your phone. All of them.

Everything can wait. If someone wants to get ahold of you, they’ll call you. This is the single biggest lever that you can do immediately today.

Deny your device the right to interrupt you.

Once you’ve done that, you can start working on making it last by engineering your environment. Here are the engineering principles that work:

1. Delegate to Human Proxies

When you see a guy like him on the plane sitting in business class, you immediately clock the type.

Let’s call him Jim.

He is an industry veteran, running his business for 40 years.

Owns a dozen HVAC businesses, makes millions in profit every year and doesn’t give a shit about anything.

You’ll know this because before you take off Jim turns to you and makes an absolutely random joke. Thirty minutes into the flight you’re hearing war stories from him while you laugh your ass off. His presence is so powerful it has gravity and forces you to be present too.

Before takeoff Jim was on the phone with someone at length. It was his general manager who runs his businesses for him. Turns out Jim hasn’t used a computer in 15 years, but he has a fully digital business, you can find him on Linkedin and ask for a quote online.

Jim doesn’t grind away online because he engineered delegation into his environment. His team IS his proxy.

All the while he spends time playing golf, travelling and playing with his grandkids.

The wealthy have always solved the attention problem through delegation. Butlers handle household demands. Executive assistants filter communications. Personal staff manage the logistics of life.

Human proxies pay attention to things so their employers don’t have to, be it arranging cleaning or your inbox.

You probably can’t afford a full-time butler.

I know I can’t.

But you can afford a Virtual Assistant for a few hours a week for starters. You can take baby steps towards the way Jim lives his life.

Work stuff a VA can handle:

Email triage and responses

Bill payments and financial admin

Social media management and posting

Calendar management

Research tasks

Non-work stuff a VA can also handle:

Ordering groceries online

Handle communications with utility companies, banks, service providers

Find specialized help or solutions when needed

Manage your subscriptions, refunds

Research and book holiday trips

This isn’t being lazy. Just recognizing that not every task deserves your attention. Some things can be handled just as well or better by someone else.

2. Create Spatial Constraints (The Phone Foyer)

Remember the early 2000s, there was a place in the house where the internet lived: the computer desk.

That was it. One location. When you left the desk, you went offline. It was easier. Nobody expected you to be always available. It was normal to wait for days to hear back from someone. You had a life and a small part of it was using a computer.

Microsoft was founded in 1975. Apple a year later. We had about 35 years of using screens without our brains boiling and then in the 2010s everything went wrong. The internet slowly started to turn to shit, literally. Enshittification is what they call it now35.

This spatial constraint was a feature, not a bug.

You can recreate it:

The Phone Foyer: Create a designated charging station in your entryway or kitchen. When you walk in the door, the phone goes there. Period. A 2020 study found that students who charged their phones next to their heads were more likely to experience sleep disturbances and daytime fatigue. Spatial distance creates cognitive distance.

The Bedroom Ban: Phones stay outside the bedroom. Buy a $10 alarm clock. This single change has been shown to improve sleep quality within weeks

The Work Zone: Define physical spaces where screens are permitted and where they’re not. The dinner table is a no-phone zone. The living room during family time is a no-phone zone.

Research on Attention Restoration Theory shows that creating “restorative environments” — spaces free from the demands of directed attention — significantly improves cognitive function and reduces mental fatigue. Your phone-free zones become restorative zones.

3. Conduct a Presence Audit

Before you can engineer intent, you need to understand your current patterns.

For one week, track every device interaction:

What device am I using? (Phone, tablet, laptop, desktop)

What am I doing? (Email, social media, work, entertainment, communication, utility)

Why am I doing it? (Intentional task, boredom, habit, notification-triggered)

Could this be eliminated? (Yes/No)

Could this be delegated? (To a VA, automation, or AI)

Could this be batched? (Combined with similar tasks at a specific time)

You’ll likely find that 70%+ of your phone pickups fall into the “habit” or “notification-triggered” categories. Those are your targets.

4. Use Tools You Can’t Hack

There’s one thing I hate about blockers and screen time limits: if you’re technical enough to set them up, you’re technical enough to bypass them.

This is the fundamental problem with software solutions. You still have the master key.

For the average person: Apps like Opal can help. Opal claims their users save an average of 1 hour and 23 minutes per day, with 94% reporting they’re less distracted.4 The “Deep Focus” mode creates genuine friction — you can’t just tap a button to disable it.

For the techie who will hack around anything: You need hardware constraints. The Balance Phone is a Samsung device with locked-down software that blocks social media, streaming, games, gambling, and pornography at the OS level. It can’t be bypassed. Their users report average daily usage of 1 hour and 17 minutes. down from the typical 5+ hours.

I’m not affiliated with them, but I switched to a Balance Phone a few months before Hanna was born. I still try to occasionally open links on it that I very well know won’t open. Just out of habit.

Make bad things hard and good things easy.

If checking Instagram requires unlocking a phone, opening an app, entering a PIN, and waiting through a cooling-off period... you’ll check it a lot less. If calling your wife requires picking up the phone and pressing one button... you’ll do it more.

5. Create Intent Triggers

Your phone is constantly triggering you to pick it up. Turn the tables.

Time-based triggers:

An alarm goes off when you’ve been on Instagram for 5 minutes

Every Monday at 8am, you receive a WhatsApp message summarizing your previous week’s screen time

A daily reminder at 6pm: “Family time starts now”

Location-based triggers:

When you arrive home, your phone automatically goes into “Home Mode” (notifications silenced, apps blocked)

When you enter your office, work apps unlock and social media locks

Behavior-based triggers:

After 3 app switches in 2 minutes, a notification asks: “What are you actually trying to do?”

When you pick up your phone more than 10 times in an hour, a prompt appears: “Put it down for 30 minutes”

The goal is to interrupt the unconscious drift into exposure and force a moment of conscious choice.

6. Change the Modality

Here’s a powerful hack: whenever possible, choose voice or video over typing.

Research from Stanford shows voice input is 3x faster than typing on mobile devices. But speed isn’t the point. The point is modality switching.

When you type on your phone, your brain is in “screen mode.” You’re one swipe away from checking email, one notification away from a doom scroll spiral. The interface invites wandering.

When you speak, your brain is in “conversation mode.” You say what you need to say, and you’re done. There’s no adjacent temptation.

Practical applications:

Send voice memos instead of texts (this is how my construction client runs his business)

Use dictation for emails and notes

Make phone calls instead of text chains

Use voice commands for searches and tasks

Voice is inherently more intentional. You have to know what you want to say before you say it. You can’t “scroll” a voice interface.

7. Build Your Butler

Everything I’ve described so far is a workaround, except for #1. But we established that we probably cannot afford a butler, so all we have is patches on a broken system.

The real solution is still to fundamentally change your relationship with the human-to-web interface. To have a proxy that handles digital life on your behalf while you stay present in physical life.

Since I’m a tech guy and I cannot afford a butler, maybe I can build one. I call it Alfred.

Alfred is my ongoing project to build a family butler. An agentic system that can act as my digital proxy. Instead of me looking at screens, Alfred looks at screens FOR me. I interact with Alfred through voice and Alfred handles the digital world.

There are caveats to this. I don’t want to keep talking to Alfred, so I want learning. I want it to build automation scripts for itself the more feedback I give. Nuances around memory, context, hallucinations. Thankfully this is what I deal with for a living as a software engineer so there’s a lot I can apply here.

The technology exists today. The challenge is integration, trust, and building workflows that actually work for a family context.

I’m building Alfred in public so you can try and do the same for your family. I have been toying around with the idea since August 2024 and this year I will commit to shipping it36.

Where I Am Right Now

This essay is my best attempt so far to make sense of presence. I’ve read the books, quoted the saints, studied the brain science, and told the stories of Roosevelt, Rogers, and Kobe. But the truth is, I’m still in the trenches with it.

My daughter Hanna is here, and too many days I catch myself reaching for the phone during playtime, or zoning out during bedtime stories because Slack pinged or a notification promised “one quick thing.”

I’m an ape with an iPhone, just like you.

I fail.

A lot.

But I’m done pretending I’ve got it figured out.

This blog, the “Screenless Dad” is my field journal.

I don’t have the keys to the kingdom.

I’m just a dad logging the experiments: what works, what crashes, what almost breaks me, and what brings me back to her face.

I’ll share the raw data: weekly screen time reports (the good, the bad, the embarrassing), the notifications I silenced, the moments I missed (and the ones I caught), the small wins and the regressions. Think build-in-public, but for presence.

“Becoming more present in public.”

I’m sharing everything here: my experiments, my work on Alfred, the fails, the iterations. If it works for our family, great. If others want to try these out, even better.

But right now, it’s just me trying to engineer presence one automation at a time.

I’m not a Screenless Dad, but I’m trying to become one.

If any of this hits home, if you’re tired of being Default Dad, or wrestling with the hypocrisy of offline rules for kids while doomscrolling yourself → subscribe.

Join the journey. Share your own numbers, traps, or hacks in the comments. We’re not fixing this overnight.

But we start by showing up honestly. Be present for your kids.

Turn your face toward them. It’s your divine duty.

Love that phone quote – worried about missing notifications while missing actual life. The irony writes itself.

I cover this kind of thing on my Substack, helping dads level up instead of just getting by. Worth checking out if this resonates. https://joewooten.substack.com/p/thriving-as-a-father

I love the idea of focusing more on the kids instead of the screens; no child should have to compete with a gadget to fight for their parents' attention.

It's a sadly interesting phenomenon. I recently discovered that kids actually face a similar problem with overflowing toy collections—they can hide behind them and miss out on real-life confrontation, discussion, and adventure. Some kindergartens even implement 'toy-free' periods to help them reset.

I was surprised to find this out, but it makes sense. Although, not all kids benefit equally, and I bet adults don't benefit equally from going screen-free either. I actually wrote more about this topic here: https://scientistmom1.substack.com/p/is-a-cluttered-playroom-the-toddler